When I was 3,

I got a train set for Christmas or a birthday. Can’t remember which, my memory is fuzzy here, but it was definitely around the time I was obsessed with Thomas the Tank Engine – even with his creepy ass face. I was fascinated: to be able to create a mini-world with mere toys and to play out scenarios with imagination alone. Without instructions or prompting, I would “choo choo!” and move the train along and create stories. According to a reputable source (mom), I played very well alone.

I remember the 요구르트 아줌마 (yogurt cart lady), pushing her yellow mini-refrigerator cart with her yellow umbrella and yellow outfit. The bell would ring through the streets and our apartment parking lot, calling children and grandmas (purchasing for their grandkids) within an earshot. They would gather with coins in hand. She’d greet us warmly, ask us about school, tell us to play nice and study hard, and to drink a lot of 요구르트. Sometimes, she would slip an extra little bottle for me. “한아 빨리 마셔라 아가!” (“drink one quickly, little one!”). I’d rush home with a slight sugar high.

In a short few years, my family and I would move to America. I would be introduced to Legos. My first set was an Old Wild West set. While I loved the cowboy, my favorite was the black plastic stallion. I’d just take the horse and gallop it all throughout my family friend’s house. Up and down the stairs, across the table, the bed, the ground, and even soar it through air – because why not?

I would learn a language nearly wholly different from my mother tongue, and become much, much better at it. I would go from “뭐라고?“ to “watchu say?” This would set me on a certain path of language barriers between me and my parents. What started as overlapping frequencies – one playing 2000s American pop and the other 1980s Korean news – would eventually turn to radio silence. They would say something in Korean; I would respond in English; we’d go back and forth until either of us gets a sniff of understanding or gives up.

I would become a Saturday morning cartoon kid. The only time I’d willingly and consistently wake up early was to catch Cartoon Network at 6:00 am. I didn’t know which show would play when, so I’d watch all of them. Ed, Edd, and Eddy; PowerPuff Girls; Courage the Cowardly Dog; Dexter’s Laboratory; Johnny Bravo; KND (Kids Next Door); Scooby Doo; Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends; and the classics, such as Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry. I’d watch any of these on repeat.

I would be on the opposite of the largest ocean. I would see faces unlike mine, and befriend them. They would say I have small eyes. I would say they smell. They would make fun of my food. I would say their food looks like plastic. They would come over, and we’d run around the yard, playing make-belief about Dragonball Z or Transformers or Star Wars. Boyhood.

When I was 13,

I changed my name from “Michael” to “Sooho.” My best friend at the time was also Michael, and we were together like white on rice. This was one of my earliest moments of agency. Reclaiming my birth name.

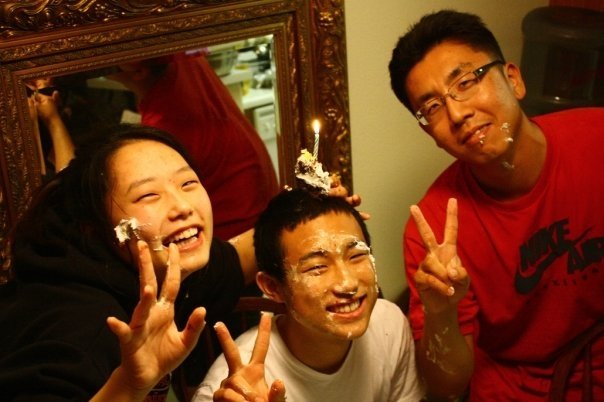

My friends became family. We bonded over games and movies (not girls, yet). Sleepovers were the best. We crammed into the game room and played co-op Halo missions, freaking out about the space zombie Flood chasing us. We fought with Super Smash Bros, and then got into real brawls. We stayed up all night, wired and zoned in to finish that annoying mission or that boss. We even went to Barnes and Noble to check out game guides and walkthroughs. We brought our desktops to each other’s houses for a lan party. I crushed them in Star Craft but got seriously handled in Counter-Strike. We dared each other to drink a concoction of lemon juice, hot sauce, mayo, coke, and sesame oil just to stay awake and play more games into the night.

In a year’s time, my parents would get divorced. I would move out of the house and live with my sisters. I wouldn’t be surprised. I saw it coming. The constant fights, both of them rarely home, the frequent flights to Korea. I don’t remember witnessing a moment of tenderness or affection between them. And it’s not like at that age my sisters and I were the glue holding the family together. We all had our own circles and lives. So, when the news dropped, I wasn’t surprised. I just asked what was for dinner.

High school would start, and I would begin one of my obsessions: bboying or breakdancing. I mean I don’t want to say I was naturally talented, but I was kind of naturally talented. Years of Taekwondo honed my internal sense of balance and translated well to holding a freeze or pulling off a power move.

It would be everything my friends and I ever did. After school, we’d rush back to either one of our houses (we all lived within a 10 min walk of each other), watch YouTube of the latest Korean bboy battles (IBE 2005 still legendary), go to the tennis courts or rec center and dance for hours.

We’d rarely study (except for the dude who got into UC Berkeley). Only subject I was decent in back then is the subject I suck the most now: math. I could have taken linear algebra (higher than Calculus BC). Now, I can’t do a simple calculation without a calculator.

I still talk to those guys. Our new obsession is F1. And I love it. We had a bit of a lull in our friendship after high school. Each of us went our own separate ways for a bit. But all it took was one short text, a shot in the dark. I didn’t even know if they had the same phone number. Anxiously I sent, “You still in SD? Wanna grab drinks?” I had no reason to be nervous. Three hours of laughter-filled yapping and beers, catching up and reminiscing. The Berkeley dude eventually moved back from the east coast, and we all got together. We got shit-faced on sipping tequila, played drunk Mario Kart, cackled till our bellies popped and tears ran down. I also got an earful for being horrendous on sim-racing. Reconnecting with them over the past few years has been a gift I didn’t know I needed.

When I was 23,

I finished college. Got dumped. Got my first car. Worked as a youth pastor. Got hit by a car. Dreamt of becoming a professor.

For most of high school, I hated studying. I was a solid average student. My SAT score was neither stellar nor abysmal. My writing was clunky and uninspiring. Reading was a bore and a drag (the only book I remember I finished and enjoyed was Handmaid’s Tale). My parents weren’t the type to care too much, and I wasn’t self-motivated enough to care. None of the subjects interested me.

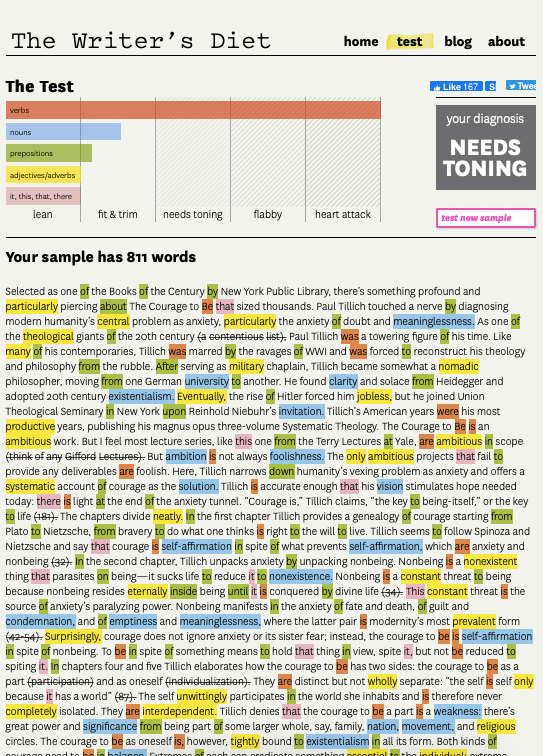

But then college came around. It was just an intro class, but for some reason I poured myself into the readings. I dug through references at the library. I underlined, highlighted, and scribbled notes. I mulled over, drafted, edited, added, edited, and fine-tuned my arguments. I aced the class with flying colors. Then the next class and the next and the next. Even some Master’s courses, I aced them too.

What happened? I became obsessed. I would hole myself up at the library and read old, obscure, ancient texts. I’d forget to eat and run on liquid caffeine. I’d see words and smell old books whenever I closed my eyes to sleep. I fell in love with learning. I entered and embraced my nerd-stage.

I once heard that ENFPs are notorious doctorate candidates. They just can’t pick a topic because they’re too interested in too many things. Surprise, surprise. I also had many iterations of research obsessions: Pentateuch (first five books of Old Testament), Job and Wisdom Literature, Johannine Studies, Athanasius, Augustine, Anselm, Martin Luther, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Søren Kierkegaard, Karl Barth, Eberhard Jüngel, Oliver Crisp, Katherine Sonderreger, Kathryn Tanner, trauma studies, post-colonial studies, and economics. (Okay, I’m name dropping, but the point is that I had many, many interests.)

This was also around the time I first watched my favorite movie (and still is): Interstellar. (I would watch it at least ten more times over the next decade.) I became entranced. I love space shit. I fuckin’ love it. Ender’s Game, Dune, Foundations, C.S. Lewis’s masterful space trilogy, Ted Chiang’s fabulous short stories, Ken Liu’s mind-bending worlds and futurism, and Cixin Liu’s near-perfect Three Body Problem trilogy. I fuckin’ love it all. Sci-fi became for me an escape into a future possibility or an alternative universe that still wrestles with human longing for love, connection, hope. And whether learning or inhabiting a fictional world, I desperately needed an escape.

I was 18, a week before spring break of freshman year, when I got a call from my sister. “Mom’s in the hospital. Get on the next flight home.” She collapsed in the middle of a parking lot and a nearby samaritan took her to the ER. I got on a flight, not knowing what happened. I landed, rushed to the hospital, and heard from the doctor’s lips: “Your mom has brain tumor.”

My sister broke down wailing while I stared out the window absent minded. It was around 4 pm. The sun was still out and annoyingly beautiful. That iridescent Southern California afternoon. I saw a mom and a boy in the parking lot; the boy skipping along while holding her hand. “I’m never going to do that again,” I thought.

After many months and years of painful memories (that I’ve written about elsewhere and don’t want to rehash here), my mom passed peacefully in 2018. While I didn’t skip, I got to hold her hand for the last time.

Now I’m 33.

The year Jesus died. He saved all of creation, and I can barely get myself out of bed at 10 am.

Some say, 30s are the prime time of life: when the seeds you’ve sown in your 20s bud and come into fruition. When you begin to see the time you’ve put into work or your craft get recognition and accolades. The labor and sacrifice you’ve sweat and bled for start to pay dividends. The long hours of self-work, therapy, and nurturing friendships mold a model, healthy, and mature human being – confident and secure in who they are and their place in the world. When surviving finally turns the corner into thriving.

…

I’m sorry, but did I miss the corner? Or is it coming soon? Is something wrong with my life’s GPS? When does it fucking turn from surviving to thriving?

“Prime time of life.“ My ass.

It’s much harder to lose weight. Got myself a little belly. Long gone are the days of eating and drinking whatever and whenever I want without consequences. Metabolism is now sluggish, so even if I eat less, I still gain and feel bloated. I probably should start running. I definitely need to start running.

Getting over hangovers? Pure misery the following two days. It’s not simple recovery anymore; it’s always survival – live or die. I imagine my entire body like the ER after a night of drinking. My brain dealing with head trauma; my liver processing overtime to pump the alcohol; my stomach churning and screaming in confusion: “Why all this shit? Why isn’t he sleeping yet?” Pure chaos.

I can’t remember a morning I didn’t wake up with some sort of lower back, neck, or shoulder pain. Sprinkle in chronic insomnia and undiagnosed ADHD and mild depression and you get a decent picture of my physical and mental wellbeing.

I’ve suffered grief, isolation, loneliness, purposelessness. Wandering aimlessly. Drowning myself in cheap dopamine to dampen suffocating feelings. I’ve contemplated suicide, but who hasn’t in our day and age. (Tangent: Men loneliness and depression epidemic is real – be sure to check in on your homies.)

“Prime time of life.“ My. Fucking. ASS.

But maybe I am getting what I deserve. If I’m really honest, I’m not the most hard working or go-getter or ambitious. I am lazy. I often dream big without follow up. I’d plan to work on stuff, but the moment I get to it I lose all motivation. I procrastinate because it’s so much goddamn easier. When I don’t want to, I just don’t. I don’t want to exercise, so I don’t. I don’t want to wake up on time, so I don’t. I don’t work on improving my craft or side-hustle or career, so I don’t. I tell myself to do things I hate, but I don’t.

And it’s not funny or cute how easily I indulge in my foibles. It’s pathetic. I eat late and drink often. I binge entertainment. Doomscroll. Brainrot. And all this dopamine dampens the mind and heart. So, while I don’t complain much (“I’m doing alright”), I don’t really know how I feel or how to feel. I fear slipping into a downward spiral of self-hatred (“You fucking deserve every bad thing, you stupid piece of shit”) if I get too critical. But I also fear that another decade will fly by, and I’ll be the same or worse off. I have fire under my ass, but I’m so numb to it that I’m melting like molten metal. The house is on fire, and I say with a stupid face, “This is fine.” But it’s not. I know it’s not.

I see my hands aged but not worn or weathered by hard labor. I look at the mirror (more often lately) and am not satisfied with what I see. My face shows signs of wrinkles from the constant pull of gravity but not from doing good and satisfying work. My eyes dull and my smile slight. “Is this how 30s are supposed to feel or look like?“

I’ve felt some real lows and continue to dip down time to time. But then again, if I’m really honest, I’ve also experienced and continue to experience real highs.

I’ve been madly in love. I’ve relished the scent and presence of another. I’ve been comforted by and delighted in another’s arms. I’ve laughed ‘til I cried and chortled so hard I fell off a chair. I’ve shed tears of relief and in response to beauty. I gleefully played in crisp ocean waves in unbearable heat. I savored umami flavors, stress-releasing spice, mind-boggling aromatics. I’d had blood course through my veins during the thrills of a damn fine show or movie. I’d had my heart thrashed and churned and stilled while reading. Rarely, very rarely, I’m proud of my writing. And I love deeply my friends and family and cherish them to the point of cathartic ache.

This is how life feels. This is how life can feel. This is how I want life to feel.

But it’s delusional to think I can go on like this: enjoying little things with little fires everywhere. So, I’m writing. I’m doing push-ups at home. I’m eating salad. I — well, I haven’t run yet, but I will. I’m putting myself out there while putting out these fires. I want to age well. I want to do things I hate so that I can love the little things more.

Life’s both the highs and lows. The boring parts and the exciting ones. The depressive dips and the euphoric soars. When you’ve got to get your shit together and use that shit to grow. I’m still growing at 3, 13, 23, 33 and onward to 43 and beyond.