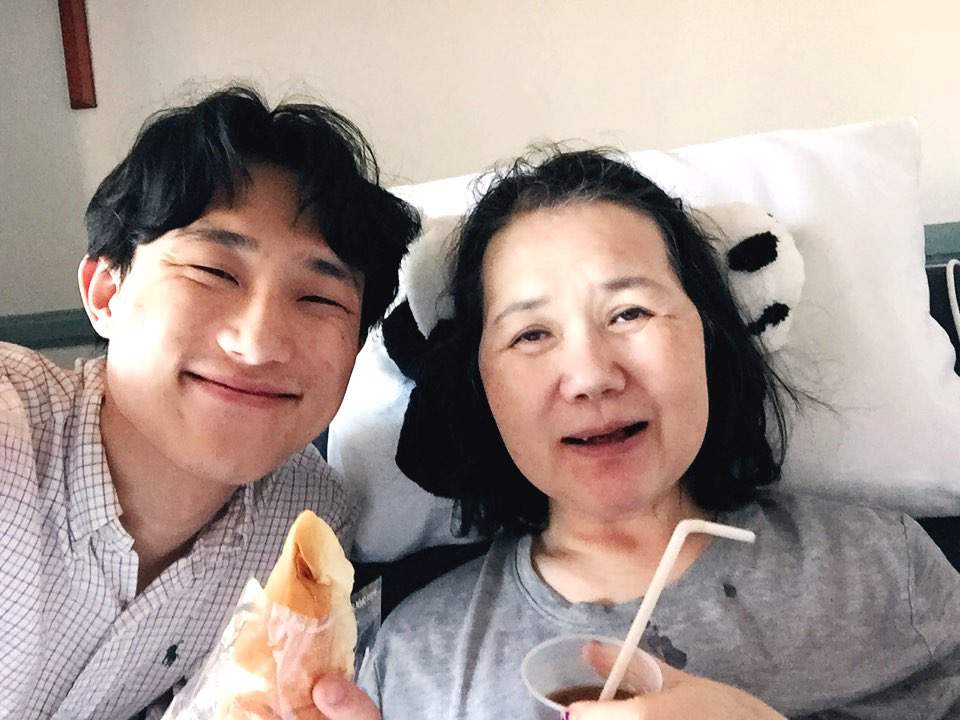

It’s my 26th birthday.

It’s also been a month since my mom passed away.

Birthdays celebrate the life that’s been given, and in partnership with my mom God gave me my life. But the timing of this birthday is both cruel and eerie. If she had died any sooner, or any later, then my 26th birthday would not have aligned with the end of my first month of mourning. So, though I want to celebrate this gift of life, I can’t help but think about the one who carried me in her womb — and also her absence. And this is cruel: today, I feel the unnerving tension between the gift of life and the loss of life.

26 years ago, she gave me life. But one month ago, her departure forced upon me a new life to live — a life without a mom.

Immediately after I got the call, I sat in my chair, trying to come to grips with what I had just heard. Then, like a deep cry welling up inside, I felt a gaping chasm:

She’s gone. She’s really gone.

On my way down to the nursing home, I realized I would not need to take these familiar roads again. On my Google Maps, I have a pin named “Mom’s Nursing Home” saved. But I will no longer need it. Though she was just one body, losing her also meant losing certain spaces and rituals, like seeing her every Sunday morning.

I was the first blood relative to see my mom’s body. To be honest, she looked scary: I saw the full terror of cancer and how it deteriorates the body. Cancer is insidious: how could cells that refuse to die be so deadly?

The room was silent; I was silent; she was silent. I broke the silence with my meager words: “I’m sorry, mom. I wish I came sooner.” I then became silent again. The silence felt more comforting. Silence is, I think, not the opposite of speaking but rather non-verbal speaking. In other words, silence still speaks, and in times of grief, silence should speak the most. So, strangely, my mom was speaking silence — the language of grief — to me, even after her death.

One of the first things I noticed after I lost her was losing my sense of space-time and reality. I kept forgetting what day of the week and time of the day it was, or even where I was. This threw off my eating and sleeping schedules. Relatedly, I kept doubting the reality of my mom’s death — Did it really happen? Did she really die?. It’s as if doubting the reality of my mom’s death — a concrete space-time event — made me lose my grip on reality. Often times, I would wake up and feel as if everything was a dream, or a nightmare. Her death was a disorienting event: whatever orientation I had of life before is gone and, ultimately, irretrievable.

I also slept a lot. There’s a misconception — I think — that grieving and mourning are purely or mostly emotional affairs, but we are embodied beings: emotions of the heart are never severed from the physicality of the body. Staying awake was exhausting enough because I would wrestle between losing a mother and accepting that it happened, and that struggle would take a physical toll on me. So, I napped a lot.

I lost some meaning-making capabilities in relation to my body. I made sense of some bodily reactions and no sense of others. For example, at random times of the day I would gag or feel an upset stomach. I questioned what my body was trying to tell me — what are you crying out? The most reasonable meaning I could formulate was how I would gag when I would feed my mom, which was one of the rituals we shared. I realized then that my body also misses her. And the most mundane things would remind me of her and make me miss her. Hearing Korean makes me miss her; seeing Korean women around my mom’s age makes me miss her; eating Korean food makes me really miss her; seeing a baby reminds me of how I was a baby in her arms; even showering reminds me of how I was bathed by her.

Oh! How I miss her!

Other bodily reactions, however, I could make little sense of. I would wake up some mornings and quickly surrender to my body’s unwillingness to move or get up: there was no motivation to do the simplest things. I still don’t know why I would arbitrarily be sapped of energy. I would also space out a lot and quickly lose concentration. One of my great joys – reading – became an arduous task.

Everything became mixed emotions. I am never just sad without being bitter, regretful, and confused. This is part of the difficulty of mourning: it’s not just that you feel one thing too much, but that you feel too many things at once, or, sometimes, nothing at all. So, language seems, at times, inadequate because it feels too confining. Sadness cannot capture the whole mess I feel. Of the many emotions, however, regret is possibly the most unwanted thing to feel during such times. But it is also the most forced upon and the hardest to shake off. I regret so many things — an overwhelming amount of things. I regret things I did and did not do — what I could’ve done but didn’t. I regret what I said and didn’t say. I regret the future possibilities that are no longer possible. And I regret that she died — silly, I know, but that’s how I felt.

This is part of the difficulty of mourning: it’s not just that you feel one thing too much, but that you feel too many things at once, or, sometimes, nothing at all.

Two years ago, I felt the call to move to California: I discerned that God wanted to teach me how to be a son and how to love a mother — both lessons I sorely needed then. But the lessons stopped abruptly in the wake of my mom’s death. One of the many mixed emotions I felt was the sense of purposelessness. I came to California and, by extension, attended Fuller to be closer to my mom. But she died and left me here. Now what? What’s the purpose of staying at Fuller or in California? Thankfully, fear (not personal wisdom) prevented me from leaving everything altogether.

It was encouraging to see so many old and new friends send their thoughts, prayers, and words. Sometimes, however, it was a bit too much. Again, everything became mixed emotions. On the one hand, I was grateful and comforted. On the other, I felt too tired to respond to each person: so, I didn’t.

Of the people who reached out to me, however, a select few profoundly touched me. One was the friend who wept with me ever since he first heard of my mom’s diagnosis, seven long years ago. Another was someone who lost his mother decades ago — and how he still mourns her absence. The former is the first person I called after hearing the news — and for the first few hours of this new life without a mother, he was my anchor. The latter is someone I deeply respect. I was not only able to glean invaluable wisdom, but also a comfort that only comes from similar experience: I felt so understood by him. And being or feeling understood is so crucial, I found: to be understood when I could not understand is a rare find and a blessing.

All this and more makes me convinced that though death is somewhat expected and normal, it is, in fact, the most unexpected and abnormal thing, precisely because death is the very opposite of life. But as I said earlier, I am forced to live a new life — one without a mother.

And, perhaps, this is the way — probably, the only way — to properly grieve profound loss: living this new life.